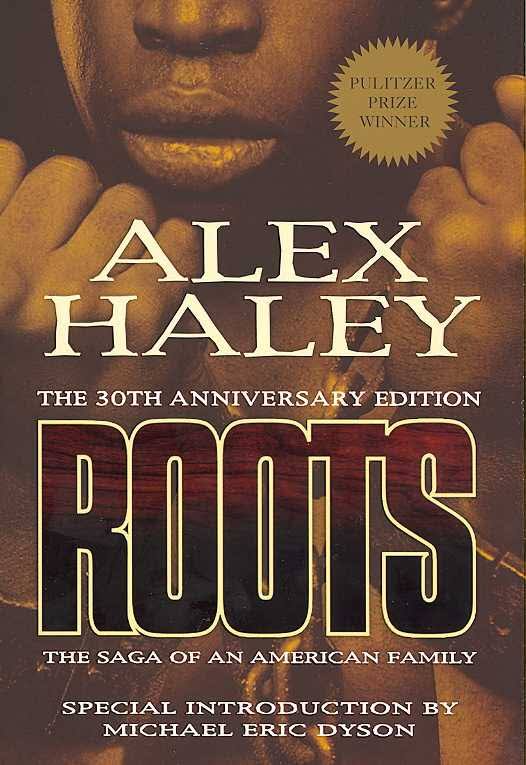

By Alex Haley

But all the children – even those as small as Kunta– would quickly scramble to sit still and quiet when the telling of a story was promised by one of the old grandmother. Though unable yet to understand many of the words, Kunta would watch with wide eyes as the old women acted out their stories with such gestures and noises that they really seemed to be happening.

As little as he was, Kunta was already familiar with some of the stories that his own Grandma Yaisa had told to him alone when he had been visiting in her hut. But along with his first-kafo playmates, he felt that the best story-teller of all was the beloved, mysterious and peculiar old Nyo Boto. Bald-headed, deeply wrinkled, as black as the bottom of a cooking pot, with her long lemongrass-root chewstick sticking out like an insect’s feeler between the few teeth she had left–which were deep orange from the countless kola nuts she had gnawed on–old Nyo Boto would settle herself with much grunting on her low stool. Though she acted gruff, the children knew that she loved them as if they were her own, which she claimed they all were.

Surrounded by them, she would growl, “Let me tell a story…”

“Please!” the children would chorus, wriggling in anticipation.

And she would begin in the way that all Mandinka story-tellers began: “At this certain time, in this certain village, lived this certain person.” It was a small boy, she said, of about their rains, who walked to the riverbank one day and found a crocodile trapped in a net.

“Help me!” the crocodile cried out.

“You’ll kill me!” cried the boy.

“No! Come nearer!” said the crocodile.

So the boy went up to the crocodile–and instantly was seized by the teeth in that long mouth.

“Is this how you repay my goodness–with badness?” cried the boy.

“Of course,” said the crocodile out of the corner of his mouth. “That is the way of the world.”

The boy refused to believe that, so the crocodile agreed not to swallow him without getting an opinion from the first three witnesses to pass by. First was an old donkey.

When the boy asked his opinion, the donkey said, “Now that I’m old and can no longer work, my master has driven me out for the leopards to get me!”

“See?” said the crocodile. Next to pass by was an old horse, who had the same opinion.

“See?” said the crocodile. Then along came a plump rabbit who said, “Well, I can’t give a good opinion without seeing this matter as it happened from the beginning.”

Grumbling, the crocodile opened his mouth to tell him–and the boy jumped out to safety on the riverbank.

“Do you like crocodile meat?” asked the rabbit. The boy said yes. “And do your parents?” He said yes again. “Then here is a crocodile ready for the pot.”

The boy ran off and returned with the men of the village, who helped him to kill the crocodile. But they brought with them a wuolo dog, which chased and caught and killed the rabbit, too.

“So the crocodile was right,” said Nyo Boto. “It is the way of the world that goodness is often repaid with badness. This is what I have told you as a story.”

“May you be blessed, have strength and prosper!” said the children gratefully.

Then the other grandmothers would pass among the children with bowls of freshly toasted beetles and grasshoppers. These would have been only tasty tidbits at another time of year, but now, on the eve of big rains, with the hungry season already beginning, the toasted insects had to serve as a noon meal, for only a few handfuls of couscous and rice remained in most families’ storehouses.

Roots by Alex Haley p. 18-20.