By James Baldwin

Excerpt from Play:

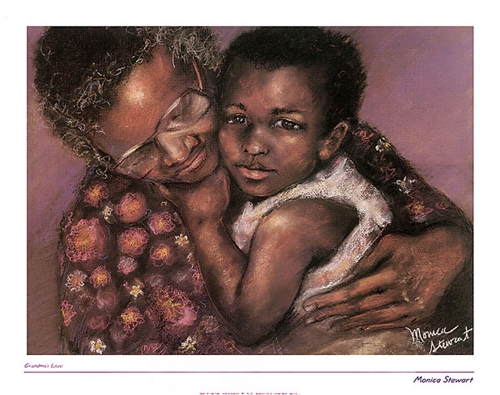

(Near the end of the song, Mother Henry enters, carrying a tray with milk, sandwiches, and cake.)

Richard: You treating me like royalty, old lady – I ain’t royalty. I’m just a raggedy-assed, out-of-work, busted musician. But I sure can sing, can’t I?

Mother Henry: You better learn some respect, you know that neither me nor your father wants that kind of language in this house. Sit down and eat, you got to get your strength back.

Richard: What for? What am I supposed to do with it?

Mother Henry: You stop that kind of talk.

Richard: Stop that kind of talk, we don’t want that kind of talk! Nobody cares what people feel or what they think or what they do – but stop that kind of talk!

Mother Henry: Richard!

Richard: All right. All right. (Throws himself on the bed, begins eating in a kind of fury.) What I can’t get over is – what in the world am I doing here? Way down here in the ass-hole of the world, the deep, black, funky South.

Mother Henry: You were born here. You got folks here. And you ain’t got no manners and you won’t learn no sense and so you naturally got yourself in trouble and had to come to your folks. You lucky it wasn’t no worse, the way you go on. You want some more milk?

Richard: No, old lady. Sit down.

Mother Henry: I ain’t got time to be fooling with you. (But she sits down.) What you got on your mind?

Richard: I don’t know. How do you stand it?

Mother Henry: Stand what? You?

Richard: Living down here with all these nowhere people.

Mother Henry: From what I’m told and from what I see, the people you’ve been among don’t seem to be any better.

Richard: You mean old Aunt Edna? She’s all right, she just ain’t very bright, is all.

Mother Henry: I am not talking about Edna. I’m talking about all them other folks you got messed up with. Look like you’d have had better sense. You hear me?

Richard: I hear you.

Mother Henry: That all you got to say?

Richard: It’s easy for you to talk, Grandmama, you don’t know nothing about New York City, or what can happen to you up there!

Mother Henry: I know what can happen to you anywhere in this world. And I know right from wrong. We tried to raise you so you’d know right from wrong, too.

Richard: We don’t see things the same way, Grandmama. I don’t know if I really know right from wrong – I’d like to, I always dig people the most who know anything, especially right from wrong!

Mother Henry: You’ve had yourself a little trouble, Richard, like we all do, and you a little tired, like we all get. You’ll be all right. You a young man. Only, just try not to go so much, try to calm down a little. Your Daddy loves you. You his only son.

Richard: That’s a good reason, Grandmama. Let me tell you about New York. You ain’t never been North, have you?

Mother Henry: Your Daddy used to tell me a little about it every time he come back from visiting you all up there.

Richard: Daddy don’t know nothing about New York. He just come up for a few days and went right on back. That ain’t the way to get to know New York. No ma’am. He never saw New York. Finally, I realized he wasn’t never going to see it – you know, there’s a whole lot of things Daddy’s never seen? I’ve seen more than he has.

Mother Henry: All young folks thinks that.

Richard: Did you? When you were young? Did you think you knew more than your mother and father? But I bet you really did, you a pretty shrewd old lady, quiet as it’s kept.

Mother Henry: No, I didn’t think that. But I thought I could find out more, because they were born in slavery, but I was born free.

Richard: Did you find out more?

Mother Henry: I found out what I had to find out – to take care of my husband and raise my children in the fear of God.

Richard: You know I don’t believe in God, Grandmama.

Mother Henry: You don’t know what you talking about. Ain’t no way possible for you not to believe in God. It ain’t up to you.

Richard: Who’s it up to, then?

Mother Henry: It’s up to the life in you – the life in you. That knows where it comes from, that believes in God. You doubt me, you just try holding your breath long enough to die.

(pages 17-19)